|

9th June 2022 Gaming night Aldershot continues with Chariot Race. As you might have guessed from the title, this game about managing railway companies in the 19th Century on a hex-based map of North America. NO WAIT, THAT'S NOT RIGHT! Chariot Race is about chariot racing in ancient Rome. That name is sure is confusing! What's in a game?

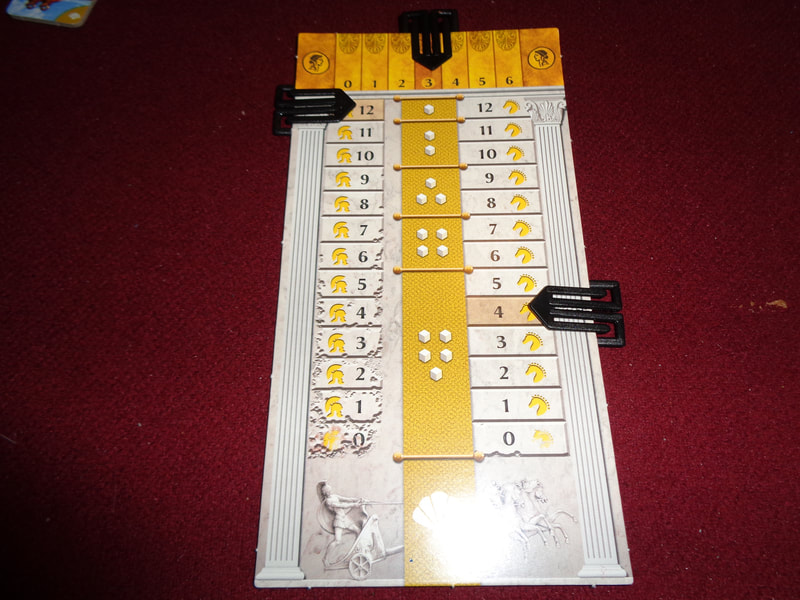

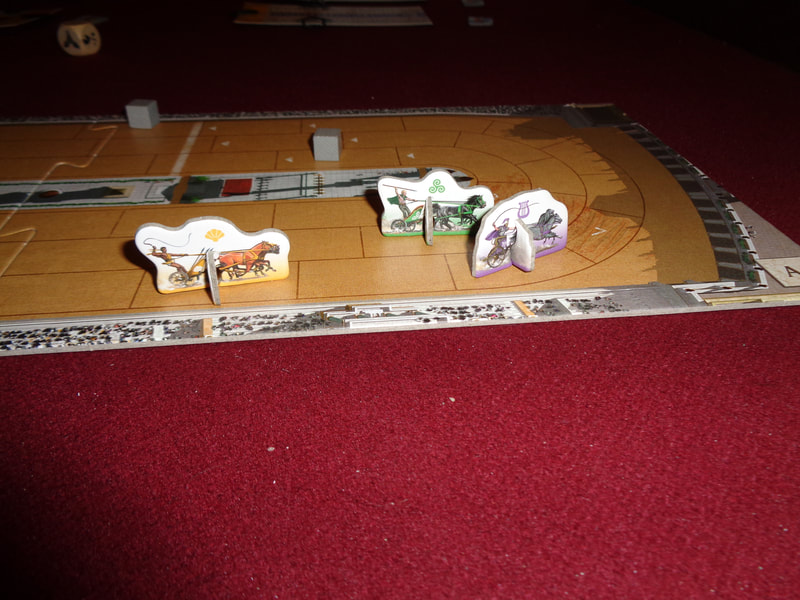

The components for Chariot Race are pretty good, the tokens and boards all feel suitably sturdy while the wooden dice are a nice touch. Having chariots made of 2 pieces or card seems a little bit of a weird choice perhaps but it's not like it's a dealbreaker or anything and was probably done to keep the cost down. There's very little artwork to write home about in Chariot Race which may be why I'm blogging about instead? There are illustrations on the chariot standees but they'll hardly be noticed since they're quite small, especially when placed on the arena/game board. There's some artwork on the game board as well and it's a fair depiction of a crowd watching the races. Otherwise Chariot Race looks fairly clean and minimalist in a unfussy kind of way, perfectly acceptable in my opinion. The only iconography that can be found during the game is on the dice, those symbols are self-explanatory and I can't imagine they'd be an obstacle to any players. Although, I will say that it feels a little odd and counterintuitive that the damage track is labelled 'damage' instead of something like 'health' since 12 on the damage track is completely undamaged and 0 is wrecked. How's it play? Setup

On to play In Chariot Race, players are attempting to complete 2 laps of the track, avoid being wrecked and of course, finish first. This is done by each player in their turn rolling dice and resolving the results. Chariot Race does not use the usual turn order. Instead it's determined by position on the track round-by-round, whoever is 1st on the track goes 1st, 2nd on the track goes 2nd and so forth. When the player in last place has gone, the round is over and play returns to the player in the lead at the start of a new round. Of course it's likely the turn order will now have changed. In their turn, the active player will have several phases they can act in.

Endgame Chariot Race is played over 2 laps and there are several criteria which can determine the winner. If a player's chariot completes their 2nd lap and no other chariot crosses the finish lap, they win the race. If 2 or more chariots finish the race in the same round, then the chariot that went the furthest past the finish line wins. Finally, a wrecked chariot cannot win, even if it crossed the finish line first or got furthest past it. Overall

Chariot Race is a fast playing and mechanically speaking, actually a fairly straightforward game; roll the dice and carry out the resulting actions displayed. The decisions that players get to make are also fairly straightforward, although their consequences can be significant - which is good. Meaningful decisions are always good. Player decisions take the form of choosing which dice to keep and which to re-roll, players must choose what to try and prioritise, this will of course be contextual and change from round to round. The other area where player's will probably be making the most is going to be about speeding up and slowing down. It's obvious that players will want to be fast in the straights but manage their speed through the race's 4 corners. Managing speed is the game's best mechanic, I like that the faster a chariot goes, the less dice the player gets to roll and consequently, the less options they have. It feels suitably thematic, not only does it represent having less thinking time at speed but also that this a horse race and players are never entirely in control of them. Players can find themselves hurtling through corners and taking damage, the question is how fast for how much damage? There's only 4 corners, so this means it's ok to take damage... right? This brings me neatly to damage. There's definitely a combative edge to Chariot Race which makes it an usual racing game. Damaging opponents has its benefits. Firstly; it lowers their maximum top speed, hindering them and secondly, it can lead to their elimination for the game. It's vital to keep an eye on damage, in the early game players will probably be congenial, but in the late game, that will all change. Having low damage points can make a player a big target, especially if that player is ahead and which others will look to exploit this to put them out of the race. It does mean that Chariot Race can have a lot of direct conflict and there may well be some 'pick-on-the-leader' tactics going on as well. If this isn't your cup of tea, it's one to probably avoid. The game also has player elimination as a mechanic, which is something I have little fondness for but fortunately, this is a quick playing game so there isn't too much downtime. In conclusion though; while it won't set the world alight, it is quick to learn and quick to play, Chariot Race is a fun light game If you like your racing theme with some extra competitive zing and a generous dollop of luck, then this might interest you.

0 Comments

19th May 2022 It's a Thursday and I'm enjoying an evening of gaming in Aldershot for the first time in actual years! Take that Covid-19! Cho chooo! Switch & Signal is a cooperative board game about managing train schedules, that's right - you're playing the generously proportion controller and how do you control these schedules. With switches and signals of course! What's in a game?

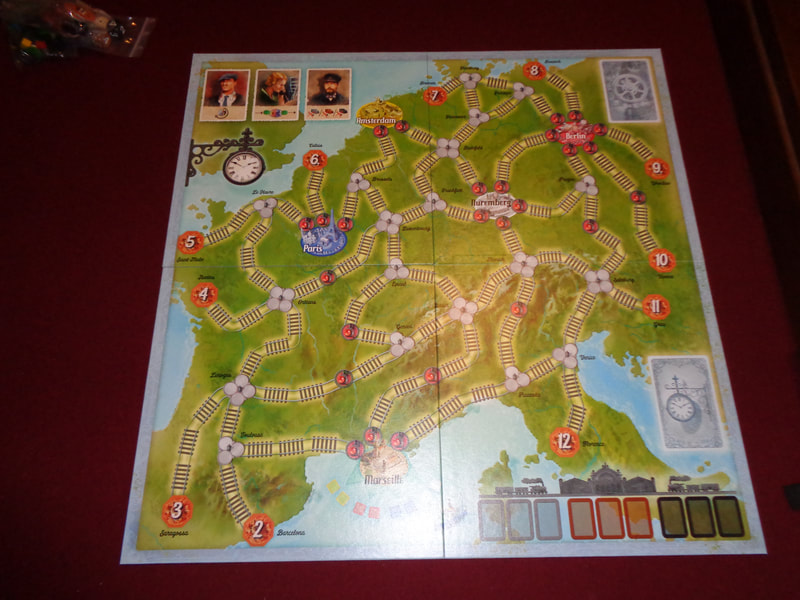

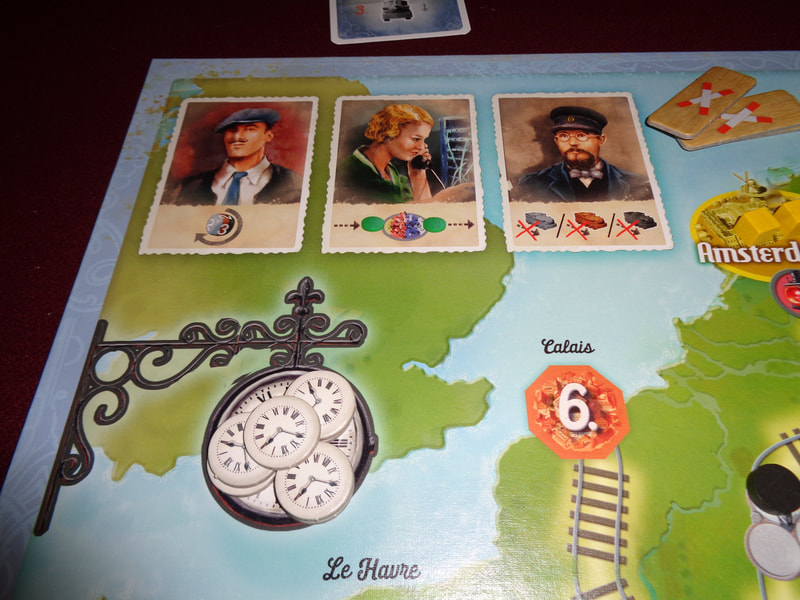

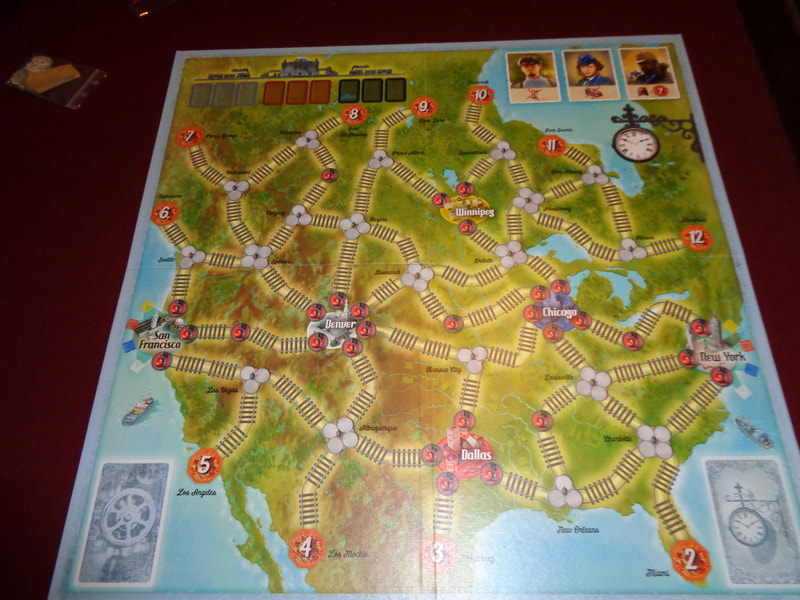

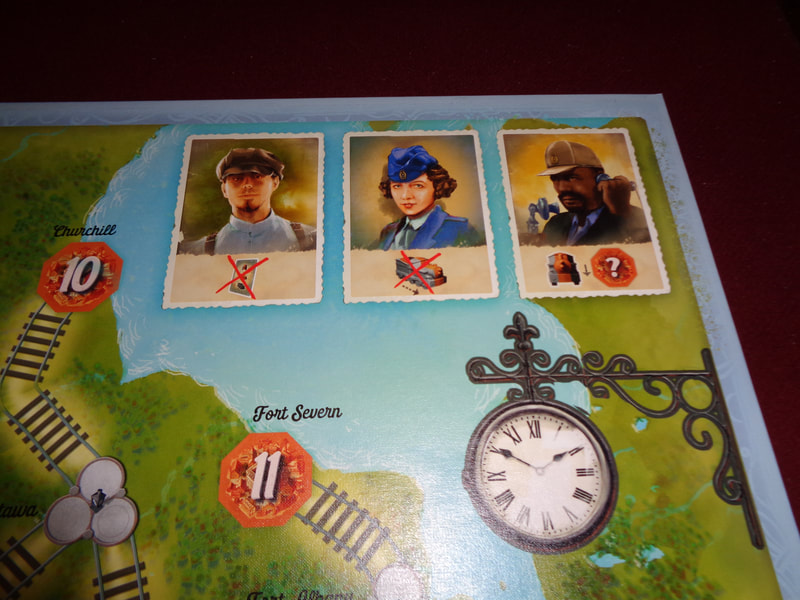

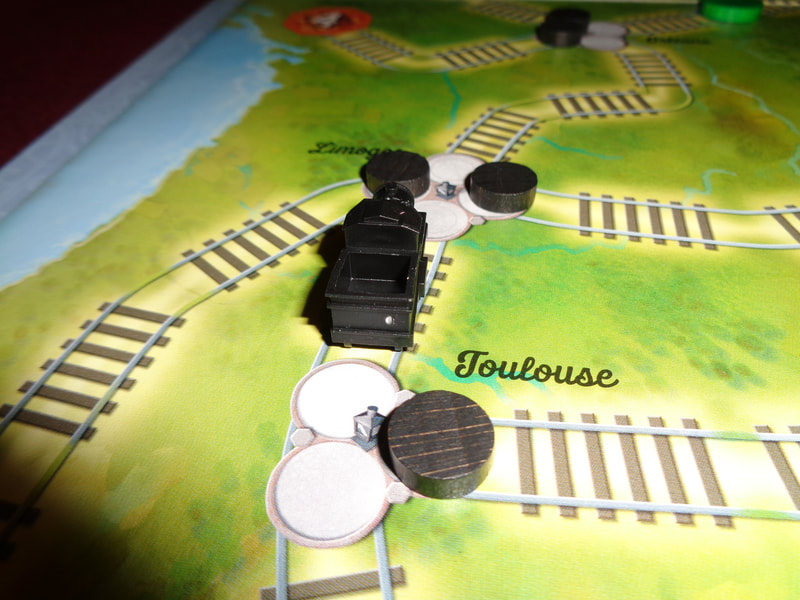

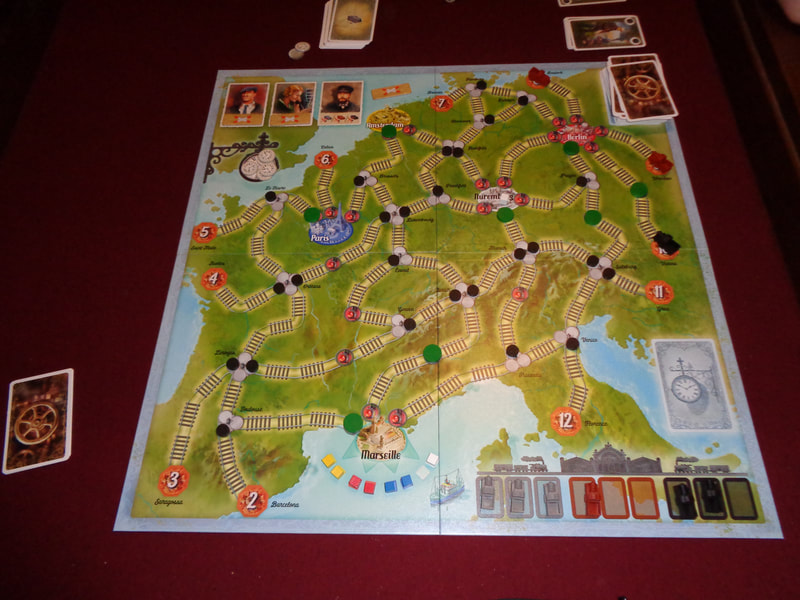

Quality-wise, all of Switch & Signal's components are made to the usual high standard we've come to expect from modern game and nothing feels particularly flimsy. The game makes good use of a wooden components, especially the dice that are nicely rounded and is something I always like. The notable components are the little plastic trains which each contain a space to put a wooden goods cube. The art is good, the boards are colourful and uncluttered with some nice illustrations for various cities. The art on the cards is equally good. The game's use of iconography is straightforward, easily understood and doesn't prove an obstacle. On to Play Setup This set up is for the European beginning default game, the rules provide options to alter the game's challenge and the U.S. side has some different rules.

On to play The objective in Switch & Signal is to collect all 8 cubes from the 4 cities using the trains and deliver them all to Marseille. Switch & Signal functions much like a lot of cooperative games; that is the active player flips a card and resolves it's actions on the board. Then the active players takes their action(s).

Endgame Play continues until one of the following conditions is met. If the players run out of departure cards and they have to draw one, then they collectively lose. If all 8 cubes are delivered, then the players immediately win. Overall

If you play a lot of cooperative games, the basic mechanics will be familiar here: Turn over a card and resolve it's action which will create obstacles for the players, then have them perform some actions and choose between progressing the objective or mitigating the problems caused by the drawing of cards. Rinse and repeat. Something about Switch & Signal feels a little different though. Maybe its because the departure cards are so contextual. The trains being moved by the departure cards are both the cause of problems for players and also the means to victory. On more than one occasion, we wanted to move a train but didn't want to spend a card to do so, instead we left it to the 'game' and departure cards to do the job for us. It's pretty rare for players to want the 'bad things happen' card to actually do something in a cooperative game. How trains are moved is vital. Not only do players have to move them into cities to pick up goods, they'll need to manage the different speeds they move at. Getting a fast train behind a slower one is a disaster, no two ways about it. This is exacerbated by the random nature in which trains are deployed on to the board by the dice. Players will also to manage the titular switches and signals. They'll look to create clear routes with full green lights to the port and funnel trains down that route in the correct order. It's a real balancing act though, it's hard to get the junction points where you want them and there's are never enough green lights. I have to say, that when it works, it feels extremely satisfying. I've never been a train controller but Switch & Signal genuinely makes me feel a little like one as I think about how to prioritise trains and set up routes with minimum card expenditure. This brings me to a final point about the game. I said earlier that being forced to discard a departure card is not good and I meant it! Switch & Signal is a well balanced game and it seemed every victory, every loss came down to the wire, came down to the last departure card or two and losing one felt very risky. I found it a lot of fun. If you like train-themed games, Switch & Signal is worth a look, how many cooperative trains games are there? If you like cooperative games, you really should give this a try. It's blend of familiar and unique mechanics makes it easy to get into yet different to other cooperative games. 25th July 2021 Sunday gaming on Board Game Arena continued with our next game. If Esther Rantzen ever made board games, it probably wouldn't be this one, for starters, there's no dog that says 'sausages'! Caveat: We have only ever played That's Life! digitally online. What's in a game? That's Life! is all about travelling along a route consisting of a series of randomly placed hexagonal tiles, where the bad ones outweigh the good ones, generally trying to manage those bad situations with a bit of luck and occasionally encountering generosity or greed. Maybe that really is what life is all about?

How's it play? Setup

On to play The goal in That's Life! is to journey to the game's end, acquiring those scoring tiles as you go while trying to avoiding those minus tiles. How's this done?

Endgame Play continues until all players' meeples have crossed the finish line. Each lucky tile acquired by a player can now used to convert the score from a minus tile into a plus, then all points are tallied, highest score wins. Overall

There's no getting away from that fact that this is a roll and move game, it may give you 2 or 3 choices from that roll, but it still is what it is. That's not to say it's all bad, usually at least 1 of the 2 or 3 choices a player is given is meaningful. Finding a way to linger on a plus tile until other players have to leave (Or getting off the tile before other players even arrive!) will earn victory points and players will obviously also want to avoid the minus tiles. However, minus tiles sort of reverses this, players will look to linger on a bad tile in the hope that another player will land it, allowing them to potentially escape. Furthermore, minus tiles outnumber plus ones 18-to-8; that's more than double, landing on them is inevitable, so is picking them up. This is what makes the lucky tiles such gamechangers with their ability to mitigate negative penalties, if a player has a lucky tile in their stack, suddenly that big minus tile becomes an asset, provided of course someone doesn't steal the lucky tile in the meantime. All of this is also largely dependant on what other players do, because they'll also be trying to linger on good tiles and escaping bad ones. That's Life! is a very easy game to learn and comprehend. I feel that it will have crossover appeal to non-gamers but for us, it felt a little too light and a little too luck-based; because players invariably end up collecting more negative tiles than positive, it ends up lending the game a negative feel - even though generally it will affect all player equally (Maybe life is like that?). It meant we didn't find That's Life a satisfying experience or a compelling game. 12th July 2019

Friday gaming in lieu of WFRP continues with the 3rd game - 'Pit Crew' We've all seen it, when a racing car pulls into the pits and the pit crew goes mental changing the tyres and refuelling the car. Pit Crew is a 'team-based' card game that attempts to emulate this frenzied burst of activity by being a 'real-time' game. How does this work? Well let's get to it. What's in a game? Pit Crew is a team based game and players will be in up to 3 teams of 1-3 people each. Thus the game supports 2-9 players. Components include:

How's it play? Firstly, all players are split up into teams of up to 3 each. Each team is given a car sheet and each team is dealt a hand of numbered cards (Split between the team players.). The objective of Pit Crew is to change the tyres and refuel your car as a team and then race it around the track on the game board. All of this is done in real time! Changing tyres To change tyres, the team must play 4 cards next to each tyre.

In order to refuel the car, multiple cards must be played on the refuelling number on the car sheet. The combined values of all of these cards must equal the value on the car sheet. Thus if the car sheet has a value of 23 for refuelling, then playing a 6, 4, 10 & 3 would equal 23. Exiting the pits Once all 4 tyres and refuelling has been completed, the car can exit the pits and enter the race. However there's a little twist here. The better the pit change, the quicker the car comes out of the pits (The more spaces it moves.). How is this calculated? This is where the colours of the cards come in play. If the cards used to change tyres are of a certain colour combination, then the car gets a bonus when leaving the pits. The same is the case for refuelling. Conversely; if the cards played on the tyres or fuel are the wrong numbers, then the car will suffer a penalty when leaving the pits. If the penalty is bad enough, the car might crash out of the game! Racing Once a car exits the pit lane and begins racing, the team rolls a die to move. This rolling is real time and the quicker they roll the dice, the more they can move. However once all cars have exited the pits, real time rolling ceases. From now on all rolling is done in turn order until the race is completed. A game consists of several races. After a race is completed, each team is given a 'bonus' card. Bonus cards confer random special abilities that can help a team or be used to hinder an opposing team. Endgame Once all the races have been run, the team that has won the most races wins. Overall Pit Crew is a small, quick and easy game to learn. Which is good, because stopping to query the rules in the middle of a real time game could prove tricky. This is the first real time tabletop game I've played and I've always been a bit suspicious of the concept. But Pit Crew was fun. I think this partially because each team plays separately and does not interfere with each other during the real time phase of the race. You have your teammates to consider! Pit Crew is a cooperative game about completing tasks quickly, but accurately in a team. The Pit Crew theme fits it very well. I think that Pit Crew is a game worth trying. |

AuthorI play, I paint. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed